Going Counterintuitive: Jeremiah and King Zedekiah

A meta on the interactions between the prophet and the king preceding the fall of Jerusalem under the Babylonian Empire

I was debating about which of two angles I should take about this story of the prophet Jeremiah and King Zedekiah of Judah circa 587 BC, which you can read from a couple of corroborating passages—2 Kings 24 and 2 Chronicles 36 that tell how the story sits in the big chronicles of the kingdoms Israel and Judah, and the close looks of events as we follow Jeremiah in the book of Jeremiah 38. The first angle was about sitting with discomfort, but the second won my heart and became the title of this post. Going counterintuitive is the high-level view of the problem in the story we’re looking at.

Note: the version of my Bible is the ESVCE (English Standard Version Catholic Edition).

In the historical books—the 2 Kings and 2 Chronicles, it’s only briefly mentioned that the king had rebelled against the law of God and hardened his heart. His disobedience and foulness in ruling had eventually led to the fall of Jerusalem, the third and final wave of exile of the Israelites in the Old Testament, under the attack of King Nebuchadnezzar of the Babylonian Empire.

However, Jeremiah 38 provides a closer look at how King Zedekiah responded. He was essentially a puppet king, installed by Nebuchadnezzar in the land of Judah. In chapter 37, we can glimpse that Zedekiah sought help from the Egyptian Pharaoh’s army to chase away the Chaldeans (used interchangeably with the Babylonians). I could imagine the tense relationship of a vassal state Judah to the Babylon, and so as a king, Zedekiah wanted a way out. Hence, the military ally in the form of the Pharaoh’s help.

Jeremiah, the weeping prophet (because of the overall sombre and depressing tone of his prophesies, understandably so given the eventual captivity), received the word of the Lord. The ancient Israeli kingdoms, the Israel in the north and Judah in the south, had prophets to speak to the kings to ensure the government upholds the Mosaic law. So, Jeremiah had conveyed to the king the words that he should hear. It was a warning that Zedekiah should not be deceived in complacency that the Chaldeans wouldn’t attack again, because they surely would and “burn this city with fire” (Jer 37:10).

The message explicitly said to surrender:

He who stays in this city shall die by the sword, by famine, and by pestilence, but he who goes out to the Chaldeans shall live. He shall have his life as a prize of war, and live. This city shall surely be given into the hand of the army of the king of Babylon and be taken (Jer 38: 2-3).

This was not the message everybody on the king’s side would want to hear. Imagine, the country was in a hostile period where it could be demolished by a much larger and more powerful empire, but the national prophet said to surrender? Come on . . .

A dissenting faction developed amongst the king’s officials who had wanted Jeremiah dead.

It was a series of punishments: Jeremiah was accused of deserting to the Chaldeans, which he didn’t, and was captured, imprisoned, and cast into the cistern of mud.

However, this is the turn of the story—showcasing how human nature reveals itself in the face of danger, Zedekiah still arranged a clandestine meeting to ask Jeremiah for the word of the Lord to devise his strategy in dealing with the Chaldeans.

The word was still the same that the king should surrender to the Babylon if he wanted his life to be spared and the city not to be burned down.

Zedekiah’s next reaction in that conversation was to divulge his fear. He was afraid of the Judeans who had deserted to the Chaldeans because these deserters might treat him cruelly. But the prophet reassured him based on the word of the Lord that the king wouldn’t be given to them.

So, there were only two options for the king to consider:

What the Lord wanted: Zedekiah to surrender to the Babylonians and stop putting up resistance—he would live

What Zedekiah wanted: the opposite.

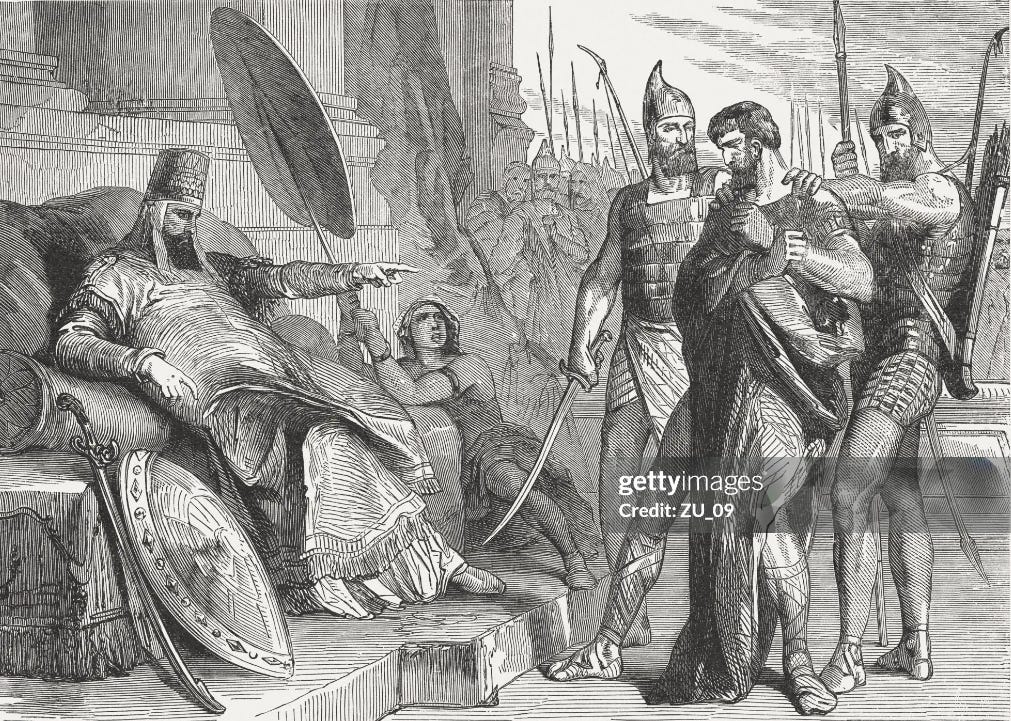

Now we could fast forward the history that his decision had yielded the worst outcome. It was not clearly depicted in the three books that he kept waging war or showing hostile attitude towards the empire, but one thing that was clear was he didn’t follow the Lord’s word to surrender. The succeeding event was Jeremiah 39 that described the fall of Jerusalem. If you’re interested, you can read from these books to know what happened to the king. Word of warning, it was violent, as the Bible didn’t hold back from this kind of description.

(the least gory image)

The Counterintuitive Action

Option 1 was the most counterintuitive action a (not-so) sovereign ruler could take. But it was the word of the Lord. It would’ve led everyone in the kingdom to a better relative outcome had the king surrendered.

Relating it to the work of God, He wants the best for us, His design is not for our harm.

But it’s human nature and ego that intervened in our willingness to follow the plan of life, leading to death. Countless verses, particularly from Proverbs, warn us about the human hubris to rely solely on our plans and not the Lord’s.

The kicker, however, is following the Lord’s plan might be against our judgment. We developed our intuition from life experience. The wisdom is based on historical lessons, of the tried-and-true, or of what could have been better if we’re given the second chance. Therefore, we might end up in a situation where our faith wants us to take a counterintuitive action that dismisses this long journey of learning. Naturally, our whole being refuses with all our might to do so.

Why do we avoid taking counterintuitive action?

We are wired for the comfort of the known

You can now see why I weighed in with two options for the title of this post, because at the heart of not wanting to take a counterintuitive action is the discomfort of the unknown.

There’s a reason why this kind of action is called the leap of faith, mainly because we don’t know what will happen. There’s no guarantee that it will result in what the messenger (the prophets, articles, etc) says. This element of uncertainty presents as a threat to our nervous system.

Our brains prefer the pathways for certainty. Uncertainties in themselves are a type of danger, on top of the tangible dangers looming in reality.

Zedekiah knew the role of Jeremiah well and he had asked him to pray for the nation (Jeremiah 37:3). His clandestine and half-effort protection signalled his faith was not entirely lost.

However, he didn’t act on it. It was at least three times the king enquired from the prophet, but it all amounted to nought.

Now, this is me going on a limb—the books tell us the account of these historical characters through their actions and words, but barely their inner workings, so I’ll apply the lens of my empathy on King Zedekiah. He must have been conflicted between following the guidance from Jeremiah and doing what was comfortable for him.

[my meta-analysis now, please bear with me]

What could have been in his mind about surrendering that made him uncomfortable, I asked myself. Well, it could be:

the loss of support from his officials—the art of ruling involves this inner political intricacy. The fear of Zedekiah of being treated cruelly by the deserters to the Chaldeans provides us a glimpse to understand his thoughts. Also, from Jeremiah 38:5, he gave Jeremiah to his officials who had resented the prophet for spreading the message of surrendering. Zedekiah seemed like a man who placed the inner court’s support highly.

the ostrich effect? This might be less plausible, but there could still be a chance that in the face of an imminent danger, Zedekiah had shut out any dissenting opinions. He might have engaged in a rigid, black-white thinking (okay, this is me projecting, I suppose), that immediately dismissed all notions of strategy that didn’t make sense in his book—even when the strategy came from the Lord.

fear of the physical and mental threats that might have been exercised upon him and his family by the captors. Despite being a legitimate fear, we knew from how the story ended that he was still taken when fleeing the siege. And what fate that had awaited him can be read in the subsequent chapter. It was the appointment of Samarra all over.

In the end, he chose to prolong the illusion of comfort by not surrendering, but he received a whole lot worse than that.

Our comfort can be anything—even something palpably uncomfortable

Zedekiah’s story can apply to our life situations as well.

Well, not everyone of us is a king ruling the ancient Judah kingdom, and it’s not every day we receive a threat from a king of the Babylonian Empire. But we face difficult moments and must take choices daily within our capacity.

This is me getting too personal, but a valid example in my recent struggle is to eat more.

I’ve been in and out of amenorrhea (absence of period) in the last 2 years, and the joke’s on me because I kept writing posts like these (I’ll attach the links at the end of this essay for you to have a look and laugh at me), and yet still fell onto the trap of restrictive eating and losing my period again.

Physically, of course, eating well is way more comfortable. But for my disordered thinking brain, my hunger signal was nonexistent. I had been depriving my body of nutrition because my “knowledge” kept quoting and finding the fact that this food increases cholesterol, that food drives insulin resistance, eating this much will give you diabetes, and so on.

Despite the danger of malnourishment being real and noticeable in my case, my fear was louder than my sense. On the internet you can find any information confirming your biases towards fear.

You want some proof that ice cream is sugar-laden and sugar drives insulin resistance? You’ll find it.

You want some proof that ice cream is essential for those in ED and hypothalamic amenorrhea recovery? You’ll find it.

It was hard to take the counterintuitive action in my case, that was, to eat more and let go of restrictions. All my “clean eating” and “health freak” behaviours have shaped my identity. It was a blasphemy to this sense of identity to buy and eat a pint of Ben & Jerry’s. The act of eating food that I didn’t normally eat was a massive threat to my brain already, on top of the undernourishment that my body suffered from.

The decision to let go and surrender

King Zedekiah’s story set off a train of thought in me about surrendering. Although the king and prophet’s story was only a snippet in the grand storyline of the Bible, it weighed on me as the reminder to let go and surrender.

Even though the point of this story was about heeding the word of the Lord and less about surrendering or letting go of control, I believe it also teaches us about surrendering in the spiritual sense.

Sometimes, what we need as a good disciple is to let go of our control. We’re short-sighted and our flawed judgement can cause utter destruction.

(Tbh, I’m also fond of the story of King Ezekiah to completely surrender to the Lord’s help, but that’s a reflection for another day)

There’s a reminder of how Judith pointed it out to Uzziah (Judith 8:16) that what he and the elders were doing was essentially giving the Lord an ultimatum—a big no.

Now, a time for reflection.

1️⃣ Do you have any experience where you needed to do something that went against your instincts or logic?

2️⃣ Have you ever avoided making a hard decision only to face greater consequences later?

3️⃣ What does surrender mean to you?

Bible in a Year

The idea for this essay came to me as I reached Day 249 of the Bible in a Year. I follow along through the Hallow app.

Let me know if you’re also on this journey so we can encourage each other.

Also, feel free to share your game plan for Lenten spiritual journey.

Before you close the tab . . .

The Gentle Roadmap is a collection of my reflections on living out faith and gentleness as a lifelong disciple. Don’t be alarmed if I write about other things as well, like food, tech, and finance, as they’re all part of the journey. If you like my writing and want to be notified of new posts, please subscribe. You’re always welcome here, regardless.

Some links about me flip-flopping all the way in healing my relationship with food:

Probably should have listened to my advice

A glimpse on my compulsive nature

Until next time,