What "When The Body Says No" Teaches Us About Autoimmune Diseases (part 2)

About poor sense of self, functional illnesses, and the role of medical diagnostics

Hello lovelies,

I hope you had a wonderful week. I’m happy spending my first week here in Aberdeen, and I had many things to be grateful for. All might sound mundane and little, but they’re blessings from God throughout the people around me, such as when I got the exact six hangers in a set, the only set left at a charity shop I just popped round. The day before, as I was unpacking, I learned I needed a minimum of six hangers for my blazers and bottoms. I wanted velvet hangers to protect the inner lining of the blazers, and the first shop I popped in after the daily mass showed me their remaining set. And behold, that set had exactly six hangers. To be fair, they were plastics instead of velvet. That was fine. I took it as my guardian angel’s inside joke.

As I’m editing this post, it’s a lovely sunny Saturday afternoon. Earlier this week, I posted about part 1 of the lessons I noted from When The Body Says No.

This week is the second part. I haven’t made up my mind yet about how many posts the entire series is going to be, I play it by ear. This week is about the call to self-reflection.

Throughout the book, the overarching theme of the trait that resurfaces as chronic illnesses is repressing emotions. Two emotions keep popping up in the patient’s stories, namely anger and resentment.

I’m familiar with both.

Lesson 6 - Stress is not subjective (again, it’s repeated)

VI. The nature of stress is not always the usual stuff that people think of. It’s not the external stress of war or money loss or somebody dying, it’s actually the internal stress of having to adjust oneself to somebody else. From Chapter 6.

In my last post, stress being not subjective is somewhat covered in Lesson 1. It’s repeated in this post as lesson 6 because the book elaborates it later to hammer it home.

Our ego, more often than not, clouds our judgement on what is stressful or not. In Chapter 6, we are taught that the measure of a stressor is based on how our body responds to the external events which serve as the triggers. It’s not an objective event itself.

Truthfully, those extraordinary events can be the source of stress. Nobody wants to live in a state of constant threats, from wars to not having enough for day-to-day living. But since we have established that stress is the biological response, it is what’s happening inside our body that manifests as psychological and physiological marks.

This is such that, to an extent, the patients interviewed in the book do not always come from exceptional threats. The way their childhood was moulded is cemented into poor sense of self to respond to the problems.

It could be that a person was raised to be a silent, agreeable young child who caused no trouble to their parents. And so, the child grows up with this internalised pattern of not making a scene. Conforming to the surroundings becomes their survival instinct to be liked and accepted.

However, keeping it all in and ignoring discourse will only brew resentment inside. The child, now a fully functioning adult, has memorised it well enough that this agreeableness and likability are what keep them afloat, from career success to a peaceful marriage.

They don’t realise that the budding resentment never goes away. It’s never spoken out or discussed with the related parties. It’s eating up their health from within.

This explanation reaffirms the sixth lesson. The issues are not addressed properly. Meanwhile, our bodily clock doesn’t have a means to rationalise the situation. It recognises the problem as it is. Although our mind can mask the resentment and order our lips to give a fake smile, our cells know and feel the stress by the work of the hormones in the background.

What’s not expressed by our mouth is a ticking time bomb for our physical health.

Lesson 7 - Drop your self-imposed poor sense of self

VII. Outwardly, people can accomplish in arts or intellectually. But on an emotional level, they have a poorly differentiated sense of self.

In conjunction with the previous lesson, those people can be accomplished individuals, renowned for their lasting legacy in their respective fields, but inwardly, they are suffering.

There is even a chapter in the book discussing the “cancer personality”, a term referring to a body of research to investigate common personality traits across cancer patients. Cancer, or any other chronic illness, manifests from the combination of different factors, including lifestyle and genes. Not everyone who smokes suffers from lung cancer. Similarly, not everyone who has a breast cancer gene develops breast cancer later in their lives. However, the internal responses of stress always play a role in the growth of diseases. Hence, this book.

The poor sense of self prevents a person from speaking up when there are problems. On the surface level, they seem amiable, their relationships are amicable, and they are well-adjusted. Those are all good qualities of a character. However, when they are achieved without a strong counterpart of assertiveness, the person reaches agreeableness by ignoring their needs, such as a spouse neglecting their own health to look after the family business, their partner’s needs, or portraying the ideal image of a family.

Not only one or two patients in the book illustrate this point. Dr Maté goes even further stating that cancer, ALS, MS, RA, and all these other conditions happen to people who have a poor sense of themselves as independent persons.

Lesson 8 - High-tech and/or medical diagnoses confirm the diseases, but don’t heal

VIII. All ills of humanity can’t be solved by yet another endoscopy (or other high-tech health check-ups). They only confirm the diseases but do not heal.

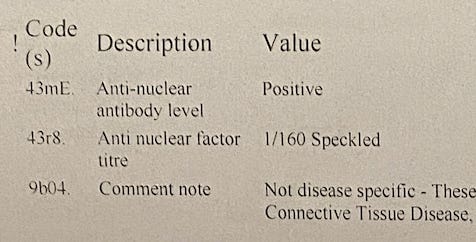

I can zoom in on my personal experience about this. Weeks ago I had a test to repeat the blood work done in my home country to record it properly in the UK system. The doctor at my GP practice explained that different countries may have different ranges and measures, so it’d be better to get re-checked here.

My result came out and it showed that my AN antibody (the character for either Sjögren’s or systemic lupus) has decreased much compared to my first SS antibody test in Jakarta.

It’s 1:160, while in Jakarta it was 1:1000.

The titre number, the number after the colon, indicates that. The higher the titre is, the higher the concentration of the antibody as it means the antibody needs more titre to virtually dilute all the antibody serum until it becomes undetected by the test. This high antibody may manifest in the physical symptoms and mysterious illnesses, in the umbrella term of autoimmune diseases.

However, my doctor concluded this new reading as normal due to understandably no severe symptoms. I take that “normal” is synonymous with “manageable”.

A side note, I’d started incorporating more CBT techniques to improve my health anxiety. Therefore, I’ll take “good enough” or “manageable”. There’s no such thing as perfect health. I feel and look healthy, and I’m conscious of keeping my illnesses at bay. That’s my narrative.

Back to the eighth lesson, the blood work and other medical diagnoses can and do confirm the diseases. They give labels. We love labels on everything, don’t we, as it’s everywhere in this society. We feel the need to put ourselves into boxes with labels. In this context, having a name for the disease is sometimes beneficial to discuss the possible treatments.

(And in a more ancient comprehension, the gnosis of a name brings power to the knower.)

Calling a disease a cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, or multiple sclerosis gives an identity to the “enemy”. It gives us the power to attack them back.

But will we heal?

What if each disease is a response to a neglected need?

Whenever I doomscroll, I stumble across posters or commenters that sound borderline boastful about how many diseases they have which become their identities. The comment section inevitably escalates to a misery Olympic, everyone tries to outdo each other by how many strange name diseases they have.

Why does it have to be this way? Doesn’t it give a signal that we’d rather live with the diseases because they give us an identity?

I need to read up on why people are militant about their misery-based labels.

But I digress. We heal holistically. The diagnoses and the subsequent treatments may help us, but the power to heal comes from within.

Lesson 9 - Functional illnesses are a chance to look inward to heal

IX. IBS is a functional illness. Functional means symptoms are not explainable by any anatomical, pathological, or biochemical abnormality or infection. As for GERD, the case is that stress may lower the pain threshold due to too many gut-wrenching experiences (hence, the phrase gut-wrenching being true), oversensitising the gut.

Following up on the eighth lesson, functional illnesses, as explained in the book, give us a chance to look inwardly to see the crux of the matter. I’m not sure if other information I saw passing around the internet is also true. It’s about which emotion corresponds with or is stored in which organ. It’s not the part of the book and I haven’t read any other books talking about the relationship. But my point is since the root cause is not explainable by a specific dysfunctional organ, why can’t we look at the system instead?

I wrote about functional hypothalamic amenorrhea.

Yes, it’s part of my autoimmune condition. But, then, so what? If we put it into a STAR (Situation - Task - Action - Result) framework here:

Situation: missing my period

Task: getting the period back

Action: ???

Result: ???

A little update: I’ve been missing my period (yes, again) since July and I’ve had enough time to introspect myself to come up with a combination of possible reasons: physical activities in London (heat + walking more than 10,000 steps every day + hauling luggage), stress of moving house (again, stress is not subjective, so according to my body, it’s a stressor), and the physical activity of going back and forth between Coatbridge and Aberdeen carrying heavy luggage and spending time on the road.

The point is: travelling is my stressor.

So, what’s my action plan?

No idea. I’ll just sit it out this one and ease out of my transitionary phase. I’m embodying more and more of staying in this new place on a long-term basis, doing my morning and evening routines, keeping my prayer and Bible study routine, and eating home-cooked meals as often as possible.

My immunologist in Jakarta gave a piece of advice that contained the key to improving my life: try working on my hormones.

It’s not about hormones prescription. Rather, balancing the responses to the stressors and keeping my body resilient. The action plan is to minimise the hormone disruptors and lower stress. We’ll see about that.

Lesson 10 - The brain-gut signals reinforcement

X. Your body sends signals if you don’t pay attention.

A part of the book describes the biological process of the gut-brain axis. The term is PNI (pyscho-neuro-immune something). It’s essentially a concept that our psychological, neurological, and immunological aspects are all connected.

It’s no wonder the health-sphere on Instagram is busy with the coaches touting about working on the vagus nerves to improve dysautonomia. Your heart beats faster when you’re on an adrenaline rush. I honestly didn’t take any notes on the adrenaline-cortisol relationship. The book says something about the opposite effect. The medication for hives or asthma, common stress responses, for instance, increases the adrenaline. But I failed to connect it to the fact that higher cortisol or stress hormone also elevates the heart rate. Anyway, I’ll share it if I find it.

Back to the PNI, in our brain, our prefrontal cortex stores emotional memories and it’s always on the lookout for danger, in the state of hypervigilance. The brain relays its interpretation of sensory stimuli to the gut, which then relays the reinforced signals to the brain.

It’s little wonder that the functional GERD must be connected to the emotional stress responses.

Bonus point: about sensitive people and health anxiety

As a sensitive person (probably an HSP at that since I fall on the more sensitive side of the spectrum), I found some explanations that illuminate my understanding of this trait.

Our ANS (autonomous nervous system) works in the background by pumping blood, digesting foods, and so on without us being aware of it. Those processes naturally cause a sound or a general feeling of something happening inside the body. A threshold must be maintained so that digestion, blood flow, and other internal mechanisms do not intrude on our lives.

You don’t want to work while your heartbeat is a constant audible sound in your ears, do you? Or that you can feel the blood circulating in your veins all the time.

Sensitive people are called sensitive because their threshold is lower. It can be a double-edged sword. On one hand, like in the book Sensitive, our sensitivity allows us to read beneath the lines, and it can be a superpower in our work or relationship. But some sensitive people are more sensitive to pains and bodily noises.

I’m more sensitive to ectopic heartbeat, for instance. Many people don’t realise they have ectopic heartbeats, but I do. Some people even only realise their heartbeat as they lay down their heads to sleep when the outside noise is minimum and they’re getting ready for slumber. It doesn’t take me that much calmness to feel it. The awareness of what my body is doing leads to a heightened urge to always catalogue the sensations.

This goes even further to worsen my health anxiety because if something feels off, I’d be aware of it and proceed with the bodily scan.

The PNI or gut-brain axis is chronically put to work in a rather self-fulfilling prophecy because the anxiety is propagated in the brain and gut. It creates a vicious cycle of internal stress and external symptoms.

I couldn’t just ignore things like my period being late, unlike my doctor friend who said “Well, if my period comes, it comes. If it’s late, it’s late.” I don’t have the capacity for the acceptance yet. I’m working on it, though, as it might hold the key to my recovery.

Dr Gabor Maté’s event in London this September

Dr Gabor Maté is going to be in London, along with Dr Bessel van der Kolk and others, for a masterclass live event this September. Dr Maté’s session is on Tuesday, 10 September 2024.

I can’t come as I still want to maximise my Aberdeen experiences for the first few months working in my new role. Stay tuned for my coming posts on the lessons.

A wee help needed

Please follow my Instagram account as I want to spread shorter content on my healing journey, especially on autoimmune conditions. Not everything is worth expounding into long-form writing, and I want to cater to those short on time and attention span by making reels or carousels.

Next post

is going to be about anger and the unique role of taking matters into our own hands in it. With today’s post length, the anger part is understandably not yet covered. Also, more about repressed emotions. (Yes, good people, alllll the repressed are resurfacing here)

Before you close the tab . . .

The Gentle Roadmap is a publication centred on feminine leadership and healing journey. The articles discuss examples of a slow and gentle approach to holistic solutions in modern life. Please consider a paid subscription to support more writing and deeper analyses.

Until next time,

I can so relate to being the smiley child. I am working on seeing what my needs are instead of what is expected of me.

It’s hard but we need to break out of the DIS-EASE.